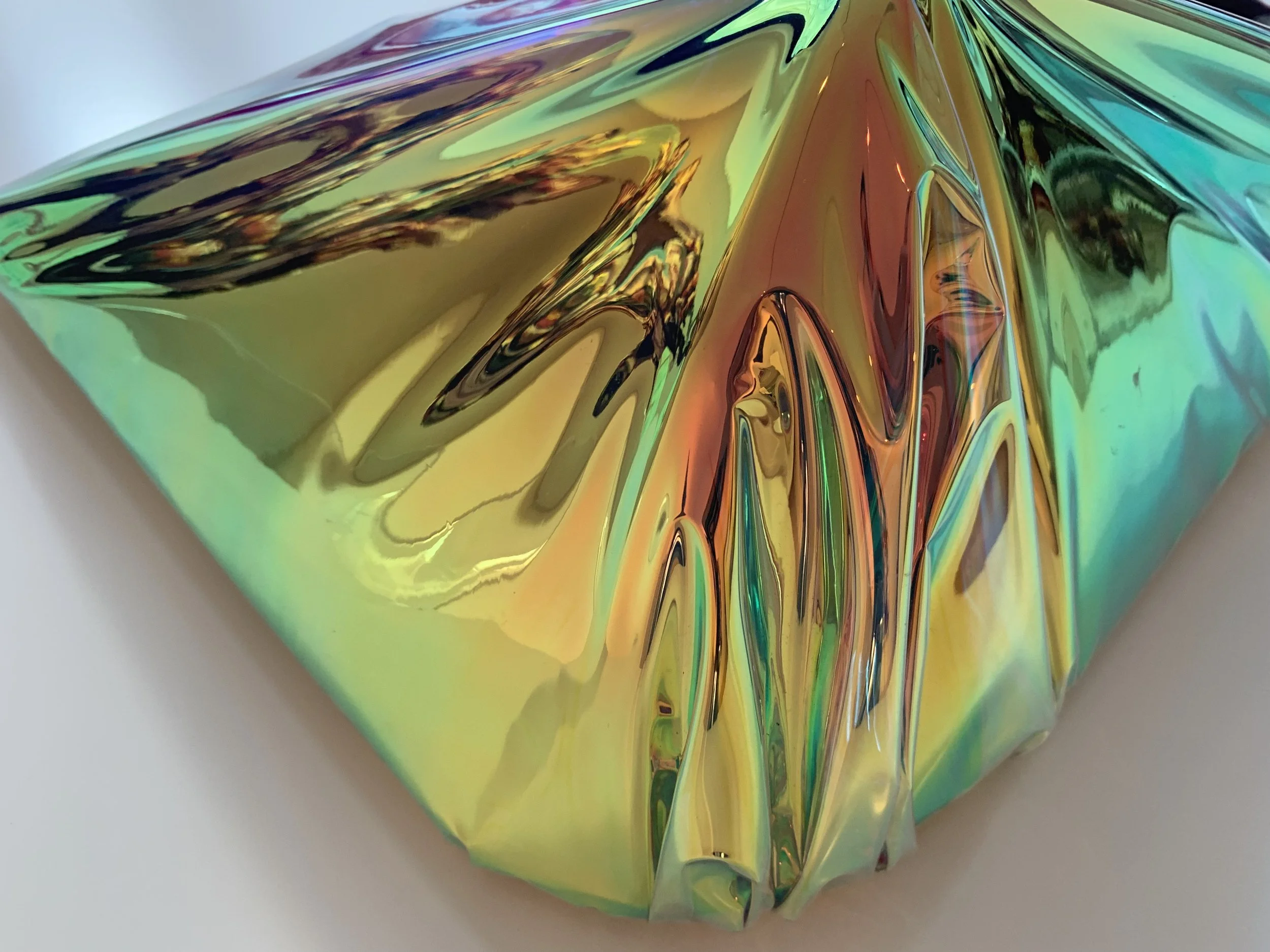

The works of Johannes Holt Iversen (*1989, Denmark) unfold within three-dimensional space at the intersection of planar objecthood, spatial light, and the viewer. Both light and the viewer exert a decisive influence on the object, altering it significantly; together they form a unity in which the elements are inseparably interwoven. Holt Iversen’s works extend beyond purely optical perception and are completed through the element of movement. Only through the impact of light does the artist’s intention become fully legible: edges, planes, and curves emerge and reflect light rays into the surrounding space; colors become visible only through illumination and shift as light moves. The resulting artworks are not confined to their physical form. They incorporate the space around them, transforming it through the immaterial, kinetic state of light and continually reconfiguring their appearance.

While light expands the work visually within space and reveals its countless facets, the viewer participates through movement, producing a purely subjective transformation. With every step—every change in distance or height of viewpoint—the object appears to shift in form, color, and intensity. The chosen materials also create a moment of recognition, as viewers can see themselves mirrored in the surface and encounter their own image in multiple manifestations shaped by texture and color. Here, the plurality of reflected selves becomes unavoidable and is, in turn, called into question. Fixing the self seems difficult—if not impossible—because with each movement and each ray of light, a different counterpart appears in reflection: at times clearly recognizable, at times distorted, at times unfamiliar. It is as though the indeterminacy of the object’s spatial condition and the multidimensional effects of Holt Iversen’s works transfer onto the viewer and their sense of self, establishing a reciprocal dependency.

This approach makes Holt Iversen’s connection to Minimal Art and Op Art—both emerging in the 1960s—immediately apparent. These movements refined the interaction between artwork and viewer through optical means. Flat color fields combined with geometric forms created calculated irritation and optical illusion, compelling the eye to differentiate a three-dimensional effect on a two-dimensional plane.

Key figures such as Richard Anuszkiewicz (1930–2020, USA) perfected these perspectival illusions and suggested sequences of movement, advocating a liberated mode of art addressed to the “open eye.” By rejecting overt stylistic signatures—such as an individualized pictorial language—attention was deliberately directed toward the work’s effect, which became a central pillar of the artwork itself.

Craig Kauffman (1932–2010, USA) expanded this principle by leaving the two-dimensional plane behind and translating such effects into physically three-dimensional formats. The optical illusions conceived in Op Art were transferred into real space—space that, in turn, is perceived as such only through the viewer’s movement. Where two-dimensional works had unsettled viewers through the absence of actual depth, Kauffman’s objects surprised by presenting real spatiality. Movement became the central motif. As a fundamental element, movement reappears in an expanded register in the work of Anish Kapoor (*1954, India), particularly in the monumental steel sculpture Cloud Gate (“The Bean”). Positioned freely in public space, Cloud Gate draws every passerby into interaction; deliberate participation and incidental encounter are equally invited, generating a dynamic that is in constant flux. Its reflective surface functions as a tool for questioning the self and habitual modes of perception.

Johannes Holt Iversen extends the traditions of Light and Space and Conceptual Art by translating these ideas into a twenty-first-century context. By foregrounding three decisive factors—light, object, and movement—his works comment on the subjectivity of perception and make visible how meaning and form emerge only through the viewer’s embodied presence in space.